Note: Louie Zamperini, who died July 2, 2014, of pneumonia at age 97, was 83 years old when I interviewed him for this long-form column which was featured in The Best American Sports Writing 2001 anthology.

Note: Louie Zamperini, who died July 2, 2014, of pneumonia at age 97, was 83 years old when I interviewed him for this long-form column which was featured in The Best American Sports Writing 2001 anthology.

My new memoir WOODEN & ME: Life Lessons from My Two-Decade Friendship with the Legendary Coach and Humanitarian to Help “Make Each Day Your Masterpiece” is available here at Amazon

THE TOUGHEST MILER EVER

By Woody Woodburn

Louis Zamperini is sitting in a café in Hollywood, not far from his home in the hills, and orders the day’s luncheon special: meatloaf.

Apologetically, the comely waitress informs him they are out of gravy for his meatloaf and mashed potatoes, expecting him to order something else. As though no gravy would matter to a man who once had no water for seven days, and no food – other than two small sharks, a few fish, and a couple birds he managed to catch while floating nearly two-thousand miles in the South Pacific – for forty-seven days.

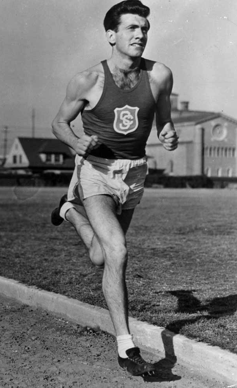

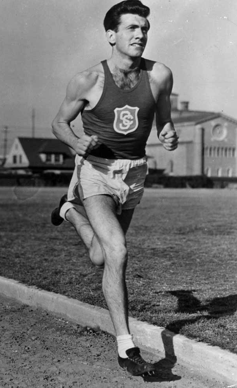

Louie Zamperini during his glory days at USC.

No gravy? That reminds Zamperini of a story. But then everything reminds “Louie” of a story. This one is about the boat trip to the 1936 Olympic Games in Germany and the recipe a U.S. Olympic coach gave him for winning a medal:

“No pork, no gravy, and no women.”

Louie’s smile tells you that he followed two-thirds of the advice.

He didn’t win an Olympic medal in Berlin, placing eighth as the top American in the five-thousand-meters, but it wasn’t because of pork, gravy or women. Rather, because of youth. Louie was only nineteen years old, freshly graduated from Torrance High School in Southern California.

Surely at age twenty-three or twenty-seven he would have won a medal in the 1940 and/or 1944 Olympics had World War II not cancelled both Games.

“In ’40 and ’44, I would have been at my running peak,” Zamperini confirms matter-of-factly, not a trace of braggadocio in his voice. “Those would have been my Olympics. I’d have brought home a medal.”

A pause: “Or two.”

And that he didn’t?

“It doesn’t bother me, Zamperini, now eighty-three, replies. His eyes remain as blue as the summer sky, but oh what darkness they have witnessed. “Not after what I’d gone through.”

Hell is what he went through.

And lived to tell about it.

Devil at My Heels he titled his autobiography, to give you an idea.

* * *

On May 27, 1943, United States Air Force Captain Louis Zamperini was a bombardier on a B-24 Liberator flying a secret experimental mission when it was shot down south of Hawaii. Eight of the eleven men aboard were killed in the crash.

Zamperini and another crewmate – the third crash survivor died in the life raft shortly thereafter – drifted nearly two-thousand miles in the South Pacific, living in terror twenty-four/seven of enemy attacks while fighting hunger, fighting thirst, even fighting sharks.

“Two big sharks tried to jump in the raft and take us out,” Zamperini retells.

That wasn’t the worst of it, though.

“We went seven days without water – that was brutal,” he adds, ironically taking a sip of iced tea before continuing.

“We managed to catch some fish, a couple of birds, two small sharks – even took their livers out for nourishment.”

On the fifth day of the seventh week, the two survivors were picked up by a Japanese patrol boat. The 5-foot-9-inch Zamperini, who weighed 160 pounds when The Green Hornet crashed, was now down to 67 pounds, and about 37 were his heart.

When the famous Olympian refused to make propaganda broadcasts for the Japanese, he was imprisoned. Ask him about the slave labor camp and Zamperini responds politely, “Those are stories for another time.”

This being lunchtime, he merely offers an answer that won’t ruin your meal or his; an answer that you can read here over breakfast; a succinct answer that says so very much: “It was daily torture, beatings starvation. It was hell.”

Hell for two and a half years.

Initially listed as “Missing in Action,” Louis Zamperini was declared officially dead by the United States War Department in 1944.

“Lou Zamperini, Olympian and War Hero Killed in Action” read one newspaper headline.

New York’s Madison Square Garden held “The Zamperini Memorial Mile.”

Zamperini Field at Torrance Airport was christened.

One problem – Louie was not dead. He was living in hell.

* * *

Louis Zamperini remembers the hell that was his very first track race – 660 yards – as a freshman at Torrance High School in 1917.

“It was too much pain. I said, ‘Never again!’ ” he retells. “I thought that was the worst pain I could imagine.”

He thought wrong.

He never imagined war, never imagined forty-seven days adrift at sea in a leaking raft, never imagined two and a half years as a prisoner of war in Camp 4-B in Naoetsu.

And, even in his worst nightmares, never imagined “The Bird.” That was the nickname the POWs gave Japanese Army Sergeant Matsuhiro Watanabe, the devil incarnate in this hell.

The Bird preyed on Zamperini, using a thick leather belt with a steel buckle to beat him bloody. In one vicious streak, he belted Louie into unconsciousness fourteen days in a row.

A devout Catholic, Zamperini’s faith was tested supremely. But, like his iron will, it was never broken.

“Faith is more important than courage,” Louie allows.

We often make sports out to be more important than they are. And yet in Louie Zamperini’s case, you cannot overestimate their importance.

“Absolutely, my athletic background saved my life,” Zamperini opines. “Track and field competition sharpens your skills. I kept thinking about my athletic training when I was competing against the elements, against the enemy, against hunger and thirst.

“In athletics, you learn to find ways to increase your effort. In athletics you don’t quit – EVER.

A sip of iced tea, and: “I’m certain I wouldn’t have survived if I hadn’t been an athlete.”

He survived hell, Louis Zamperini did, but this hero – an authentic hero, mind you, not one created by Nike – was never the same athlete after Camp 4-B.

“My body never recovered,” he shares. “My body was beaten.”

His body weighed just eighty pound at war’s end, sixty-seven pounds below his racing weight. The Olympic Games resumed in 1948 without Louie. He never won the Olympic medal – or two – he once thought he would. But he was a mettle winner. He had already proved himself to be the toughest miler who ever lived.

The Toughest Miler Who Ever Lived will be the honorary starter for today’s seventh annual Keep L.A. Running 5K and 10K races at Dockweiler Beach in Playa del Rey. The event is expected to raise $100,000 for various charities.

It is not a one-time good deed. Louie Zamperini has been working with youth since 1952, taking them running and camping and skiing, and most importantly, taking them under his guidance.

Top this day he gives a couple speeches a week at schools, churches, and clubs, reaching out to as many as three-thousand youngsters and teens a month.

* * *

The sixty-plus-year-old scrapbook, its leather cover cracked and the spine long ago broken, shows the wear of passing decades much more than does the man who was the boy featured inside.

Louie Zamperini, who in January began his eighty-third lap around the sun, turns the pages the tattered pages chronicling his athletic life. Here he is in Torrance High where he set a national schoolboy record. There he is in Berlin for the 1936 Olympics where he represented America proudly. Here he is at the University of Southern California where he was twice the national champion at the distance of one mile.

The scrapbook is about the size of a large couch cushion, and just as thick, with yellowed newspaper clippings from the defunct Torrance Herald and The New York Times and more. But the amazing thing is that this glorious memorabilia very nearly could have been a long and inglorious police rap sheet instead.

“I was a juvenile delinquent,” Zamperini says, confessing to belonging to a gang, to stealing pies and food and, this being the Depression and Prohibition, even breaking into bootleggers’ homes to steal their illegal hooch.

“At fifteen years of age, it was really touch and go,” he continues. “My parents were really worried. My dad, my (older) brother Pete, the principal, and the police chief all got together and decided track was the thing to straighten me out.”

This seemed a strange choice, because other than fleeing from the law, young Louie had shown no aptitude for running.

“At picnic races, the girls beat me,” Louie shares, laughing at the distant memory. “I hated running. ‘Boy,’ I thought, ‘this is not for me.’ ”

His first track meet didn’t change his thinking.

“I came in dead last in the 660 behind a sickly guy and a fat guy. The pain and exhaustion. The smoking, the chewing tobacco, the booze – I was a mess.

“Running? ‘Never again!’ ” I said.

Never came just a week later. Coerced into competing in a dual meet as the only 660-yard runner from Torrance High, Louie again found himself in last place.

“I didn’t care,” he retells, “until I heard fans cheering, ‘Go Lou-EE! Go Lou-EEE!’ When I heard them cheering my name, I ran my guts out and barely passed one guy.”

The moment mattered.

It matters still.

“That’s the race I remember most fondly, even more than the Olympic race in Berlin, more than the NCAA titles,” Louie says, the memory warming him like the summer sun.

More fondly than the Olympics?

“Yes, truthfully,” he rejoins. “You have to understand, that race changed my life. I was shocked to realize people knew my name. That was the start. You never forget your first anything, and that was my first taste of recognition.”

Cue the Rocky theme music.

“Instantly, I became a running fanatic,” Louie points out, and proudly. “I wouldn’t eat pie or ice cream. I even started eating vegetables.”

And he ran. Everywhere. He ran four miles to the beach. And four miles back. He ran in the mountains, sometimes while hunting rabbit (so his mom could cook rabbit cacciatore) and deer, running up the steep slopes with a rifle slung over his shoulder.

His unique training methods worked. Soon he won a race. And another. Once without direction, he now had one forward, fast.

As a sophomore in 1933, Louie set a course record (9 minutes, 57 seconds) in a two-mile cross-country race, winning varsity by a quarter-mile. He didn’t lose a race – cross-country or track – for the next three years!

En route of the amazing streak, as a junior, Louie broke the national high school record in the mile with a 4:21 clocking. If the time on a cinder rack doesn’t overly impress you, this surely will: his mark stood for a full twenty years.

* * *

Impressive, too was being invited to the 1936 U.S. Olympic Trials at the tender age of nineteen.

Unfortunately, the Trials were across the country in New York.

Serendipitously, Louie’s father worked for the Southern Pacific Railroad and annually received one free round-trip pass good for any destination. In a scene seemingly borrowed by Hollywood ten years later in It’s a Wonderful Life, Torrance (population 2,500) merchants donated a suitcase and new clothes to the local hero and even some money for food and lodging.

Skipping the mile – “Glenn Cunningham and a few others ran around 4:10, so I thought I had no chance” – Louie entered the five-thousand-meters instead. Smart move. “The Iron Man,” as one newspaper headline referred to the thickly muscled Zamperini, tied for first place to make the Olympic team.

He was not so wise during the long – and luxurious – ship trip across The Pond.

“My big mistake was eating all the good food until I was too heavy to run,” laments Zamperini, who roomed with the great Jesse Owens. “I put on ten to twelve pounds. I ate myself out of a medal.”

Still, he might have turned in the greatest eighth-place showing (in a field of forty-one runners) in Olympic history.

“My brother had always told me, ‘Isn’t one minute of pain worth a lifetime of glory?’ ” Louie shares.

He got his glory thanks to a final minute of pain.

Actually, only fifty-six seconds of pain, that being how quickly Louie ran the final lap. Running his guts out like he had in that high school race when he finally beat a runner and heard his name cheered aloud, Louie gained fifty meters on the winner and passed so many runners that Adolf Hitler was so impressed he asked for the Italian kid from America to be brought up to his box to shake his hand.

After the Olympics, Zamperini took his racing spikes to USC.

With no mountains to climb while pursuing rabbit and deer, Louie would scale the fence to the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and run up and down and up and down the stairs “until my legs went numb.”

It worked like magic.

He became a two-time NCAA champion in the mile (1938-39), the first mile champ ever from the West Coast. His mile mark of 4:08 stood as the national collegiate record for 15 years, but it almost was a mark for the ages.

“I didn’t even push it,” Zamperini allows. “I was so mad at myself afterwards. I could have run four-flat.”

Four minutes flat? In 1939? A full fifteen years before Roger Bannister would make history by breaking the four-minute barrier?

“Yes. I know I could have run four-flat that day,” Zamperini insists.

Even if he had, that feat wouldn’t have been half as remarkable as what he did do: survive for forty-seven days adrift at sea in a raft; surviving seven straight days without water; surviving on a couple of birds and little sharks and big courage; and then surviving daily torture in as Japanese slave labor camp for two and a half years.

His older brother Pete miscalculated, and greatly. Louie’s lifetime of glory came at a considerably steeper price than sixty seconds of pain.

* * *

“Age has a way of catching up to you,” says the man who never saw anyone catch up to him from behind on the cinder track.

Actually, Louie Zamperini seems to be outrunning Father Time, too.

Louie Zamperini with the Olympic torch.

Sure, the thick, dark, curly hair on the dashing young man seen on page after page in the oversized scrapbook has thinned and turned white. But watch Louie, princely in posture still, nimbly climb the flight of stairs to his second-floor office at the First Presbyterian Church of Hollywood and you can almost picture him, even in his eighty-third summer, chasing deer up a coastal mountainside with a rifle slung over his back.

Louie closes the book of memories and then shares one more from the pages of his mind: “Gregory Peck once sent over a bottle of champagne to my table with a note: ‘Race you around the block.’

“We didn’t, of course.”

In his day, Louie Zamperini was the fastest around the block, but the most amazing thing is not the national prep mile record he set that stood for two decades or his collegiate mile mark that stood for fifteen years, nor the glory of competing in the Olympics or even surviving forty-seven days lost at sea and two and half years more in hell.

No, the most amazing thing of all is this: “I forgave The Bird,” Louie Zamperini, sitting in a Hollywood café, tells you, and he means it.

In fact, he tried to arrange a meeting with Watanabe – who had avoided prosecution as a war criminal by hiding out in the remote mountains near Nagano until the statute of limitations ran out – during the 1998 Nagano Winter Olympics. Alas, the extended olive branch was crushed under the heels of Watanabe’s family members.

The hell of Camp 4-B was a lifetime ago.

Lunch on a heavenly July afternoon is now.

No gravy?

No matter.

The Toughest Miler Who Ever Lived smiles at the young waitress and orders the meatloaf anyway.

* * *

Woody Woodburn writes a weekly column for The Ventura County Star and can be contacted at WoodyWriter@gmail.com.

Check out my new memoir WOODEN & ME: Life Lessons from My Two-Decade Friendship with the Legendary Coach and Humanitarian to Help “Make Each Day Your Masterpiece”

Zeus was the God of the Sky in ancient Greek mythology, so it seemed like a smile from the heavens to visit Greece’s Olympia ruins – including the Temple of Zeus – under a cloudless sky as blue as the nearby Ionian Sea.

Zeus was the God of the Sky in ancient Greek mythology, so it seemed like a smile from the heavens to visit Greece’s Olympia ruins – including the Temple of Zeus – under a cloudless sky as blue as the nearby Ionian Sea.

Personalized Signed copies of WOODEN & ME: Life Lessons from My Two-Decade Friendship with the Legendary Coach and Humanitarian to Help “Make Each Day Your Masterpiece” and “Strawberries in Wintertime: Essays on Life, Love, and Laughter” are available at WoodyWoodburn.com

Personalized Signed copies of WOODEN & ME: Life Lessons from My Two-Decade Friendship with the Legendary Coach and Humanitarian to Help “Make Each Day Your Masterpiece” and “Strawberries in Wintertime: Essays on Life, Love, and Laughter” are available at WoodyWoodburn.com