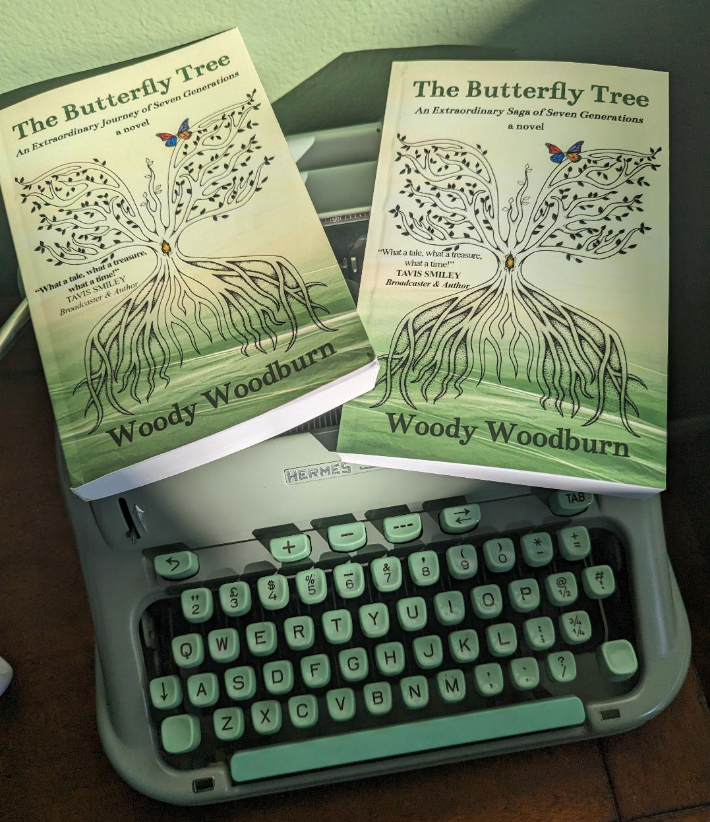

Woody’s new novel “The Butterfly Tree” is available at Amazon (click here) and orderable at all bookshops.

“Life imitates art,” Oscar Wilde famously asserted and his words proved eerily accurate a month ago when my 97-year-old father, a surgeon turned patient, was battling cancer to the courageous end.

One night, after Pop’s breathing had grown shallower by the day and more and labored by the hour, I read him the excerpt below from my newly released novel “The Butterfly Tree: An Extraordinary Saga of Seven Generations.”

*

“What I want you to promise me,” Doc said—breathe—“is that you’ll grieve only one day for me.” Breathe. “After one day, dry your eyes and focus on always remembering our good times together”—breathe—“and never forgetting how much I love you.”

Tears bathed his twin sons’ cheeks.

“There’s something I never told you”—breathe—“and probably should have,” Doc, now 83, continued weakly, pneumonia’s grip growing strong. With effort he proceeded to share the depths of his long-ago widower’s bereavement and suicide attempt, including the exploding ether bottle that awakened him the night his house burned down. “So you see”—breathe—“you boys saved my life.”

“We had no idea,” said Lemuel.

“We’ll still never say who really started that fire,” Jamis said, impishly.

“I have my suspicion,” Doc retorted, winking intimately at Jay-Jay.

Turning serious again: “As I’ve often told you, try to make each day your masterpiece. Breathe. If you’re successful doing that most days, day after day and week after month after year”—breathe—“when you get to the end of your adventure you’ll have lived a masterpiece life. Breathe. I’ve made some flawed brushstrokes, certainly, but all in all, I’m pleased”—breathe—“with my life’s painting. Yes, I feel happy and fulfilled. My only real regret”—breathe—“is that it’s all passed by so swiftly, in a blink it seems. Breathe. I feel like I did when I was a kid on the pony ride at the fair”—breathe—“I want to go around one more time.”

Jamis leaned over and hugged Doc, embracing his Pops longer than he ever had, and still it was far too brief. Lem, lightly stroking Doc’s left arm, suddenly realized the brushstroke-like birthmark resembled Halley’s Comet—The tail of a comet that Grandma warned us would bring tears, he thought.

Doc slept for most of the next two days, awaking only for short spells—including evening shaves from the town barber, Jonny Gold. Breathing became more labored as his failing lungs slowly filled with drowning fluid. During Connie’s illness long before, and again with Alycia’s not so long ago, Doc lovingly told them it was okay to “let go” rather than suffer. But he found it impossible to grant himself similar merciful permission.

Jamis and Lem gave it instead.

“Keep fighting if it’s for you, Pops,” Jamis said, his tone tender as a requiem. “But if you’re doing it for Lem and me, we’ll be okay—go be with Aly and Connie. We love you beyond all measure.”

“We’ll never forget your love,” Lem whispered, his lips brushing his namesake’s ear.

Doc opened his eyes, blue-grey like the ocean on a cloudy day, and with clear recognition grinned fragilely at Jamis, then at Lem, letting them know he heard their lovely words. His eyelids lowered shut as he squeezed his sons’ hands and whistle-hummed, almost inaudibly, before being gently spirited away.

*

When I finished reading, and then echoed the twins’ words with my own, my dad opened his ocean-hued eyes, briefly; smiled, faintly; gave my hand a tender squeeze, lengthily; and death imitated art before my next visit the following day.

* * *

Woody’s new novel “The Butterfly Tree” is now available in paperback and eBook at Amazon (click here), other online bookstores, and is orderable at all bookshops.

*

Essay copyrights Woody Woodburn

Excerpt from “The Butterfly Tree” by Woody Woodburn, BarkingBoxer Press, all rights reserved, now available at Amazon and other online booksellers and many bookshops. Woody can be contacted at woodywriter@gmail.com.

*