Woody’s highly anticipated new book “STRAWBERRIES IN WINTERTIME: Essays on Life, Love, and Laughter” is NOW available! Order your signed copy HERE!

Woody’s highly anticipated new book “STRAWBERRIES IN WINTERTIME: Essays on Life, Love, and Laughter” is NOW available! Order your signed copy HERE!

* * *

Peak and Valley at Mount Vernon

This is the final in a four-column series chronicling my recent father-son road trip to the homes of two Founding Fathers – and more.

* * *

George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate is the most popular historic home in America with more than one million visitors annually. People make the pilgrimage to see the 21-room mansion, the spectacular panoramic view of the Potomac River and, of course, the tomb where the “Father of Our Country” rests eternally.

Paying respects at the white marble sarcophagus, adorned with a raised eagle and shield and the simple inscription “Washington,” was a far more emotional experience than I had anticipated. The moment filled my heart with esteem, my eyes with moisture.

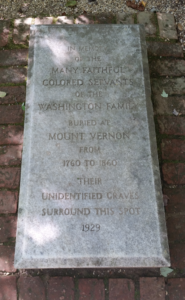

Arched entryway to the Slave Memorial and Burial Ground at Mount Vernon.

Following a brief downhill walk into the nearby woods, a few of the pooled tears overflowed. My son and I were at the Slave Memorial and Burial Ground.

A red-brick archway, similar to one at Washington’s Tomb, serves as an entrance to a lovely tree-shaded clearing. At the end of a narrow pathway is a cylindrical stone marker bearing this inscription: “In memory of the Afro Americans who served as slaves at Mount Vernon this monument marking their burial ground dedicated September 21, 1983.”

The marker rises from a circular stone foundation, framed by manicured shrubs, and adorned with three words around its perimeter at the 2 o’clock, 6 o’clock and 10 o’clock positions: “Faith”, “Hope” and “Love.”

At the Mount Vernon Museum, faith, hope and love were joined by heartbreak, tribulation and injustice in the “Lives Bound Together” exhibit documenting slavery at the plantation.

In its own right, the exhibit is powerfully moving. I found it fivefold so because a young family consisting of a father, mother and three sons – the oldest being age 10 – were perusing alongside me and at the same pace. Moreover, the African-American parents took turns reading the information plaques aloud to their sons.

For example, the dad read this: “George Washington was born into a world where slavery was common. At age 11, he inherited 10 enslaved people from his father.”

He then explained to his eldest son: “That would be like you, on your birthday next month, inheriting 10 slaves.”

I am not certain about the son, but this statement hit me like a flush roundhouse.

“Most enslaved people never had the opportunity to become literate,” the mom now read, adding: “If they did manage to learn, they could be punished for it. Can you imagine being whipped for learning to read?”

And so it continued for an hour, a history lesson becoming more painfully real because slavery could very possibly be in this beautiful family’s roots. I felt a rising anger and disappointment at Washington.

And so it continued for an hour, a history lesson becoming more painfully real because slavery could very possibly be in this beautiful family’s roots. I felt a rising anger and disappointment at Washington.

And yet, to his credit, Washington recognized marriages between his slaves, even though the law did not. He also did not separate enslaved families.

Too, importantly, in his will Washington freed upon his death the 123 slaves he owned. It can be argued this was too little, too late, but also know this: of the Founding Fathers who owned slaves, Washington is the only one to give emancipation.

In his eulogy for Washington on December 29, 1799, Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, put this final deed into perspective: “Unbiased by the popular opinion of the state in which is the memorable Mount Vernon – he dared to do his duty, and wipe off the only stain with which man could ever reproach him.”

Earlier, sitting contemplatively at the Slave Memorial and feeling downhearted about our greatest Founding Father’s ugly “stain,” something beautiful happened. All afternoon, walking the grounds from hilltop to riverbank, I had seen one lone butterfly – at Washington’s Tomb. Now, I spotted a second, fluttering above the stone marker honoring the slaves.

Butterflies serve as the archetype of metamorphosis and a symbol of resurrection. So it seemed fitting to see these two butterflies – or was possibly it the same one? – as a metaphor, not only for how our country changed in regards to slavery, but also how George Washington did.

* * *

Woody Woodburn writes a weekly column for The Ventura County Star and can be contacted at WoodyWriter@gmail.com.

Check out my new memoir WOODEN & ME: Life Lessons from My Two-Decade Friendship with the Legendary Coach and Humanitarian to Help “Make Each Day Your Masterpiece”

Check out my new memoir WOODEN & ME: Life Lessons from My Two-Decade Friendship with the Legendary Coach and Humanitarian to Help “Make Each Day Your Masterpiece”

- Personalized signed copies are available at WoodyWoodburn.com

- Unsigned paperbacks or Kindle ebook can be purchased here at Amazon